The work of Frank Lloyd Wright was abundantly influential in shaping America’s architectural legacy, with his projects leaving their mark on almost every US state. These historically and architecturally significant projects have now been interpreted into colourful artistic depictions, expertly illustrated by artist Muhammed Sajid for Home Advisor. Some of the featured properties have now been demolished, damaged or renovated, but these powerful representations restore each original concept in precise tonal graphic form. The evocative collection stands to remind us of how the iconic designer’s tremendous portfolio will forever be entangled with American culture… “The mother art is architecture. Without an architecture of our own we have no soul of our own civilization”– Frank Lloyd Wright.

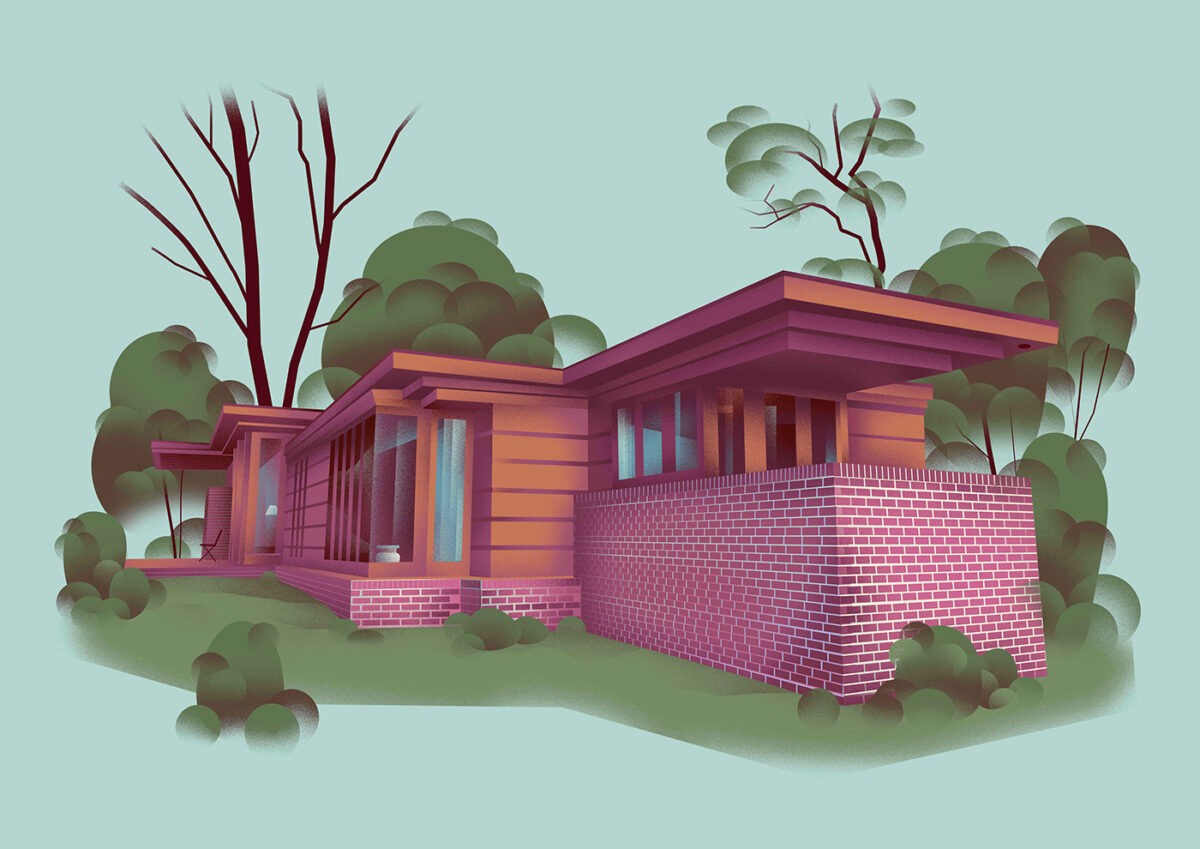

Running alphabetically through 37 states of Frank Lloyd Wright legacy, we begin our gallery in Alabama. The Rosenbaum House was the first design to draw from the Usonian Jacobs House prototype. 63 years later, the house became a museum for original Wright designed furniture.

In Arizona, one of Wright’s rare spiral designs was built for the architect’s son and daughter-in-law, David & Gladys Wright. The house plays upon a shape that would later evolve into the 1959 Guggenheim Museum.

Wright’s Usonian and Prairie designs were key in changing the way that domestic houses were constructed. This Usonian Bachman-Wilson House was relocated away from flood threat by the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas.

The Hollyhock House in California was Wright’s first West Coast design. It showcases a style born from Asian, Aztec, Maya and Egyptian architecture that Wright coined California Romanza.

The Rayward-Shepherd House in Connecticut is a horseshoe-shaped house, idyllically situated beside a waterfall on the Noroton River. The house’s official name is ‘Tirranna’, an aboriginal Australian word for running waters.

A cantilevered roof overhangs coursed fieldstone at the Usonian style Dudley Spencer residence, Delaware.

This pod-shaped home was Wright’s sole residence in Florida. The Lewis Spring House shares curvaceous characteristics with the Guggenheim museum, which was created at the same time.

This example of Wright’s passively heated & naturally cooled solar hemicycle design was brought to life in Hawaii in 1995, decades after Wright’s death.

The parallelogram-shaped Archie Teater Studio in Idaho, AKA Teater’s Knoll, is a single open plan room.

The long horizontal lines of the Avery Coonley House was designed to mirror the flat vastness of the Illinois prairie. Its exterior of colored patterns precedes Wright’s textile block houses of the 1920s.

Inspired by Wright’s first trip to Japan, Indiana’s K.C. DeRhodes House features a sloping roof like those in traditional Japanese architecture.

Eye catching dark-wood framework attractively wraps the corners of Iowa’s Stockman House. The house would later become a museum after being saved from demolition by a proud local community.

A hint of Japanese aesthetic weaves through the Allen–Lambe House in Kansas, as Wright was simultaneously designing the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo.

After meeting Wright during a ship voyage, Reverend Jesse R. Zeigler commissioned this Prairie-style house in Kentucky based on Wright’s article “A Fireproof House for $5000” published in the Ladies' Home Journal in 1907.

Designed for Wright’s own son, this hemicycle home in Maryland features concentric and intersecting curves around an almond-shape structure.

Of four homes that Wright built in the Upjohn pharmaceutical company’s cooperative community in Michigan, the Robert & Rae Levin House was the first.

Although Wright never visited the site of this house in Minnesota, the notable Elam House is the second-largest Usonian design ever built.

Operable windows distributed cooling breezes around the elegant Charnley-Norwood House, Mississippi, on which Wright worked as a draftsman alongside designer Louis Sullivan.

It was third time lucky on the design of the Harvey P. and Eliza Sutton House in Nebraska, after Eliza rejected the first two.

Rows of rectangular windows perforate the white concrete Usonian Automatic facade of the Toufic H. Kalil House, New Hampshire. Wright’s Zimmerman House stands on the same street.

In new New Jersey, the pitched roof of the J.A. Sweeton Residence is only four feet from the ground at its lowest point.

The intriguing Arnold Friedman House in New Mexico features Wright’s first attempt at a teepee concept, roofed with cedar shakes.

The elongated ‘T’ shape of the E.E. Boynton House in New York was the result of a successful collaboration with the owner’s 21 year old daughter, Beulah.

A solid example of Wright’s Prairie style, Ohio’s Westcott House has a linear silhouette with a long roofline.

Built for the architect’s cousin, the 10,000 square feet Richard L. Jones House in Oklahoma is a larger example of Wright’s work, which features a pool, fish pond and fountain.

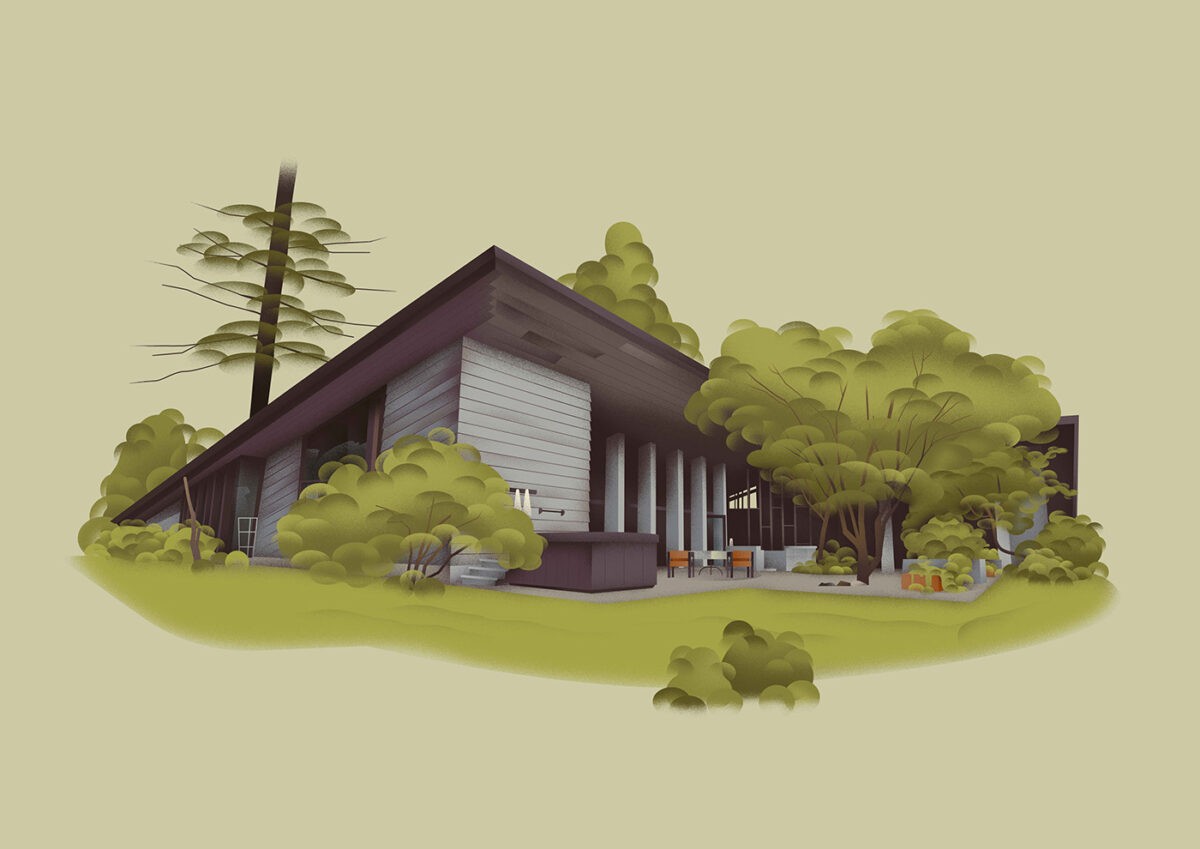

In Oregon, the Gordon House was saved from destruction to be opened as a museum for unique fretwork.

“Study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you” said Wright, and the Fallingwater masterpiece in Pennsylvania conveys this harmonious mindset perhaps more than most of his works.

In tune with the old oak trees around the 4,000-acre Auldbrass Plantation in South Carolina, the exterior house walls climb at a gentle slope.

Planted at the top of a hill with views of the Tennessee River and Lookout Mountain, the Usonian Seamour and Gerte Shavin house has stonework reminiscent of Fallingwater.

A hexagonal copper dome tops the grand living room of the Gillin residence, Texas. This was the very last home completed before Wright’s death.

An L-shaped Usonian design, the Virginian Pope–Leighey House has moved position twice! The first move was to escape the expansion of Highway 66, the second a move of just 30 feet to escape soil instability.